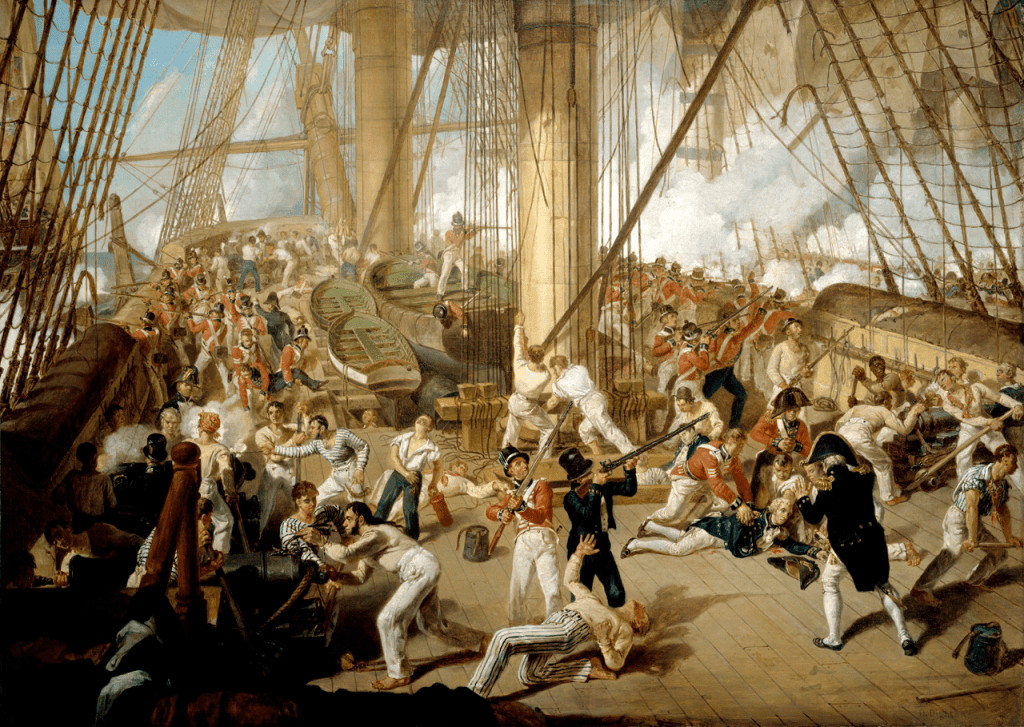

You might have read this week about two pictures of Nelson being taken down from the walls of Parliament.

This is one of them:

The suggestion – from the newspapers, at least – is that the pictures were removed in an attempt to ‘modernise’ and ‘decolonise’ the artwork in Parliament. I don’t know if journalists are deliberately stoking the fire, but some have suggested that the Nelson pictures have now been replaced with portraits of current-day success stories such as Home Secretary, Yvette Cooper (whose comparative successes, I confess, have passed me by).

As regular readers will know, I am not an historian by trade. My aim for this project, and my upcoming Nelson biography, is to tell his story to a new audience. However, such has been the swelling tide of negativity towards Nelson recently, I now feel slightly duty bound to also help preserve his honour (as puffed up as such a notion sounds for an oik like me).

There are plenty of crooks in British history. Horatio Nelson is not one of them. Flawed, absolutely. But in no way is he deserving of the mud currently being flung his way. And whatever one thinks of his character, to attempt to wash away or even underplay his contribution to Great Britain is almost to rewrite history as some sort of warped chatroom fan fiction, driving the narrative in a direction one thinks it ought to go, rather than dealing with the reality.

As you sit there now, scrolling through this on your phone, it is easy to discard events of two hundred years ago as irrelevant. But the defeat of Nelson and the Royal Navy by the French in 1805 would have changed our lives today to the point of them being unrecognisable.

Napoleon was so confident of invading Britain that he had this coin minted to celebrate in advance:

The French on it translates to ‘Invasion of England’ and, along the bottom, ‘Struck in London, 1804’. On the reverse is a profile of Emperor Bonaparte.

Across the continent, country after country had submitted to Napoleon’s invading forces. The only thing holding him back from marching French soldiers up through Kent and onto the streets of London was the slip of North Sea between his country and ours. The water wasn’t an issue in and of itself, so much as who was patrolling it: Nelson and his navy.

By 1805, French and Spanish naval forces had united to create a superpower of the sea. Invasion panic gripped Britain. When the government asked Nelson to sail out to meet this combined fleet head-on at Cape Trafalgar, Spain, he was told he would have fewer ships than the enemy, far fewer men, and no time. And he had to defeat them on a scale never before seen in the history of sea warfare.

If Nelson failed, Britain was finished.

In the days before sailing off to meet his enemy, and his fate, Nelson was mobbed by adoring crowds in shops and on street corners. ‘I had their huzzas before,’ he told a friend amidst the cheering, ‘I have their hearts now’.

He carried the weight of a nation. Heavier still, he carried their expectation.

Those who knew Nelson best knew of his inner worries. His career and private life had taken their toll. One-armed, one-eyed, thin, and sallow, he looked years older than 47. One contemporary noted how he trembled so much that the rings shook on his fingers.

But something about sticking one on the French always brought out the best in Horatio Nelson. When he met with the waiting British fleet at Trafalgar, he did what he had always done. He swelled hearts and got his men primed to defend their keep. His tactics were clear and easy to follow. Everybody knew their part. Everybody felt important.

Nelson’s performance at Trafalgar was his masterpiece, the culmination of his decades at sea, since stepping onto his first warship as a nervous twelve-year-old. It was a masterclass in man management, tactical nous, and raw – arguably stupid – heroism.

I don’t use the word heroism lightly. A man of his rank had every right to watch the fight unfold from the rear, but Nelson hungered to get in amongst the gunsmoke. He was genuinely annoyed that his ship, HMS Victory, had only been second into battle that morning, not first.

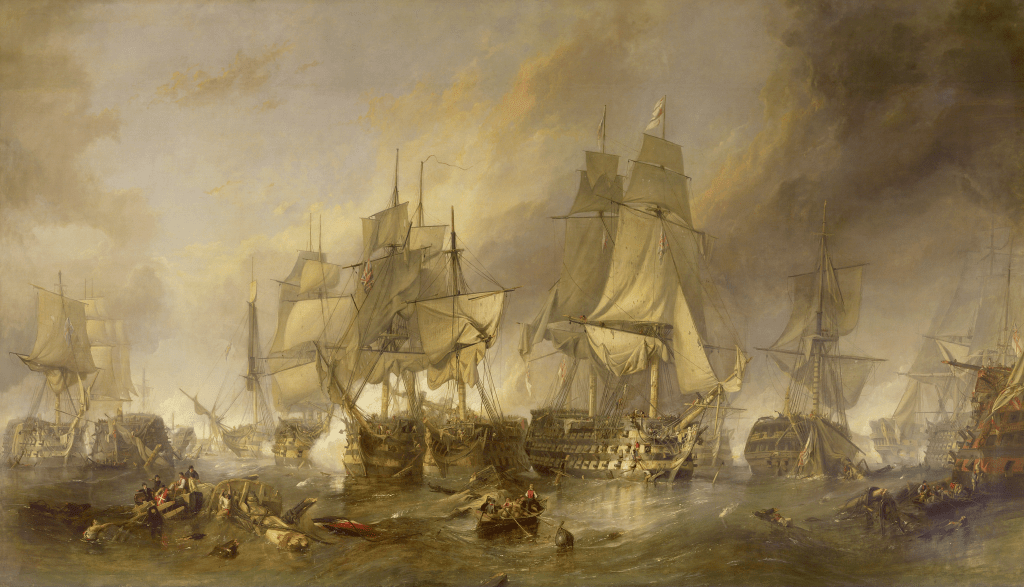

The British entered the Battle of Trafalgar with 17,000 men; the enemy, 30,000. The opposition ships outnumbered the Royal Navy’s by 33 to 27.

By late afternoon, though, Nelson’s men had battered the superior French and Spanish fleet to such an extent that people didn’t quite know what to make of it. The numbers were so overwhelming as to border on the abstract. The enemy had lost eighteen of its prized warships. It was unheard of. More strikingly, the Royal Navy had lost not one.

Nelson had stepped up when a terrified Britain was at its most desperate. Napoleon’s celebratory invasion coin would never enter circulation. At Trafalgar, Nelson had paid the ultimate price in answering his government’s call, bleeding to death after a rogue sniper’s bullet caught his shoulder. Two centuries later, his government feels so uneasy about him that we’re told they have taken a painting depicting his death off their wall.

Nelson knew fame was fickle, but he would be devastated to see his acts of bravery now counting against him. And genuinely bemused as to the reasons why.

Perhaps in two hundred years, someone like me will be thrashing out enthusiastic online blogs about Yvette Cooper and the enormous role she played in salvaging Great Britain from the depths. Until then, it’s only fair that some of us stand up for Horatio Nelson.