When trying to drum up a suitably seasonal tale on the subject of Nelson, the pickings are slimmer than a Quality Street tin in early March. For those modern-day moaners who lament the loss of the traditional Christmas, it’s worth remembering that for hundreds of years, up until the mid-Victorian era, Christmas celebrations were comparatively slight, and bore little resemblance to our imaginary concept of whatever a traditional Christmas is.

What I’m trying to say is, sadly, I can’t rustle up much in the way of an image of young Nelson and his family playing charades by the fireside or lighting candles on a tree (a practice that makes me shudder with visions of house fires). These yuletide traditions wouldn’t catch on until Nelson was long buried in the St Paul’s crypt (hence the hideous AI image at the top of this piece).

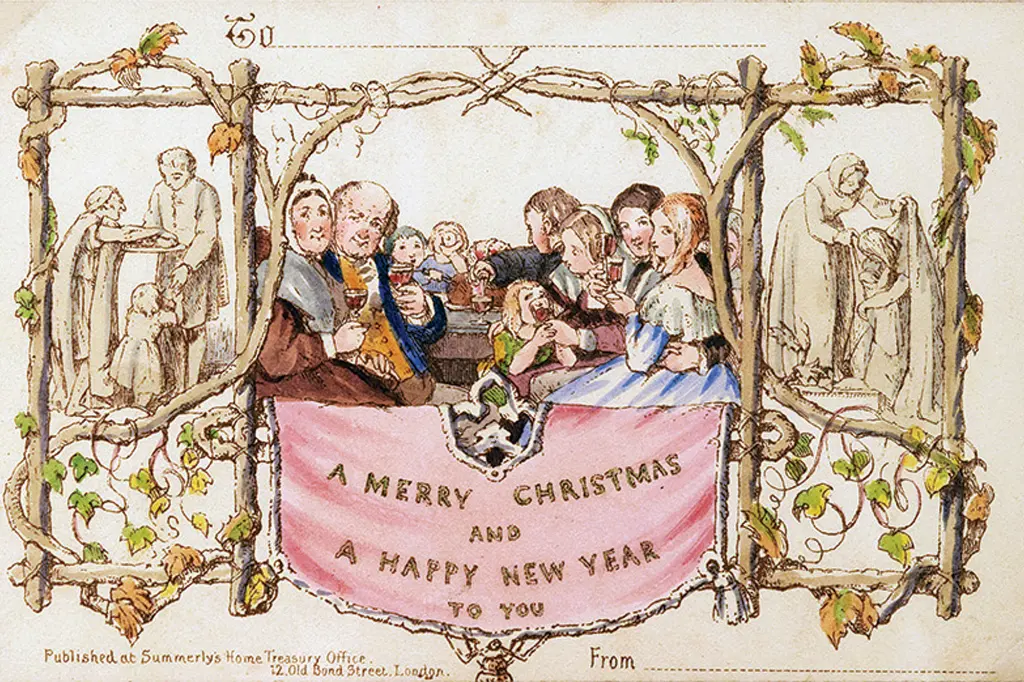

However, there is one quick story worth sharing. It involves Nelson and a Christmas card. Well, a Christmas letter, really, but whatever. (Christmas cards were another invention of those godly Victorians. That said, the first Christmas card included a picture of a toddler being force-fed a goblet of port, which isn’t especially godly, on the whole.) The letter was sent to his famous sea-faring uncle, Maurice Suckling, in December, 1770, when Nelson was still a Norwich schoolboy – and still known as Horace, not Horatio.

Many middle class Georgian parents, particularly those with financial constraints, were keen for their sons to be ‘brought forward’. In other words, to have them thrown headfirst into adulthood, out of school and into apprenticeships, often with the armed forces.

The young Nelson was so keen to swap classroom for boat deck, that he suggested bringing himself forward. He had read in the Norfolk Chronicle newspaper of his uncle, Maurice Suckling’s, attempts to staff his latest ship, HMS Raisonnable.

‘Do, Brother William,’ Horace is said to have pleaded, ‘write to my father at Bath and tell him I should like to go with my uncle Maurice at sea.’

Brother William acquiesced and sent a letter to Bath, where their widowed father, Edmund, was holidaying solo. (Here’s another sign of Christmas’s former lack of importance: that a father might leave his motherless children to be looked after by the house-staff during the festive season’s business end…) Unlike today, the cost of postage was to be paid by the recipient, not the sender. The frugal Edmund may well have been annoyed by this unexpected demand for coinage, but not only did he part with the relevant fee, he also acted upon the letter’s contents, sending a direct missive from Bath to his celebrated in-law, Maurice Suckling, in London.

Suckling – himself likely peeved at having to dish out hard cash to read a letter he never asked for – then scribbled back to Edmund (who was by now probably having to dig behind the sofa to find money) a note containing words that have made it into seemingly every Nelson biography since.

Here’s what Maurice Suckling’s famous letter said:

‘What has poor Horace done, who is so weak that above all the rest he should be sent to rough it out at sea? But let him come; and the first time we go into action a cannon ball may knock off his head and so provide for him.’

Horace Nelson’s Christmas letter had worked. In the ensuing spring of 1771, his time as a schoolboy came to a close. He was to become a midshipman. Aged twelve.

The world has changed a great deal since that December of Nelson’s childhood. Christmas is now all-consuming, cannon balls no longer knock children’s heads off, and the cost of one Royal Mail stamp is more expensive than several chariot rides to Bath. But the years of mad adventure immediately ahead of little Horace Nelson after Christmas, 1770, would provide a personal change so fulsome they would practically render him a different entity. Even his name would be altered, from Horace to Horatio.

Or should that be, Ho-Ho-Horatio?

I’m sorry.

Merry Christmas!