When William Wilberforce was asked what he should like to abolish after slavery, he is said to have replied, ‘The Lottery!’

It may surprise some to learn that there even was a lottery in Georgian times (and that it was sometimes called the ‘National Lottery’). The Georgian lottery wasn’t weekly, nor was it hosted by Anthea Turner, but it was immensely popular. Between 1694 and its demise in 1826, there were 170 official ‘State’ lotteries.

Organised by the Bank of England, ticket prices varied and sometimes cost the equivalent of £500 today. The jackpots could get as high as £20,000 (well over £1 million in modern money). Like today’s lottery, the jackpot was occasionally won by syndicates, groups of working class men and women who clubbed together to buy a ticket. One such club described themselves as consisting of ‘a few Christians, some Jews, and a number of heathens’. Others put adverts in papers, pleading for fellow contributors to share the cost – and windfall – of a ticket.

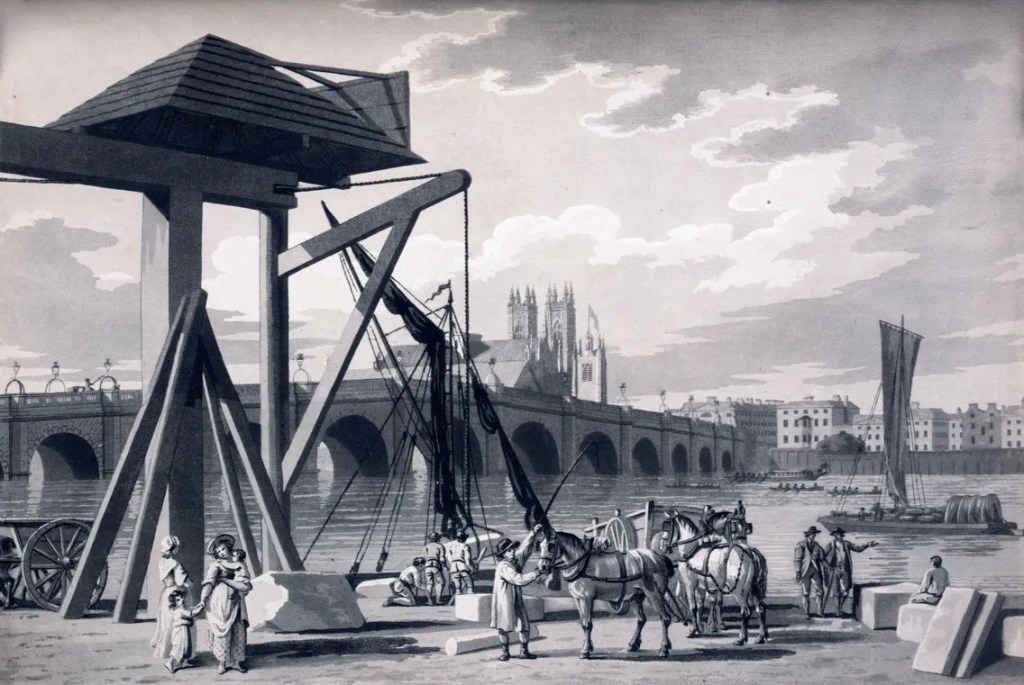

Whereas today’s Lotto raises funds for British victories at the Olympics, Georgian lotteries raised funds for British victories on the battlefield. With a good deal of 18th-century lottery profits going towards rearmament, buying a ticket was almost viewed as an act of patriotism. But there were more philanthropic uses for the cash, too. Both Westminster Bridge in the 1730s, and the British Museum, in the 1750s, were funded by lottery money.

Numerous biographers have noted how Horatio Nelson, in his early adulthood, regularly bought lottery tickets, particularly when living on half-pay. That he’d had a string of rejections by wealthy young women would have likely been a driver in his eagerness to win big.

I only bring the subject of the lottery up because I keep seeing a TV ad for a recent £15 million jackpot. I almost never play the lottery. An old man once said to me, in passing, that he wins on the lottery every single week. His secret? To not play it. He proudly told me that this tactic brings him in a cool £52 a year. Whenever I have played, though, it has always been with a dose of desperation, during one of life’s low ebbs.

It’s worth remembering that for all the accusations thrown towards Nelson as having been a beneficiary of that dread word privilege, money was seldom something he had much of. He was forever feeling he needed to play catch-up with his genuinely affluent peers, even to the point of buying lottery tickets.

The practice eventually had its day, however. As history tells us, William Wilberforce didn’t like to back a lost cause. The lottery was duly abolished in 1826, the year Beethoven composed his String Quartet No.14 in C# minor. It wouldn’t return until 1994, when Pato Banton duetted on Baby, Come Back with UB40. The culture may have changed, but this new National Lottery proved every bit as popular as the first.

You can find out more about the mighty William Wilberforce at the Hull History Centre. It opened in Wilberforce’s hometown in 2010. Funded, naturally, by the National Lottery.

It’s what he would have wanted.

I think…