I confess. I’ve never really known precisely when harvest festival is.

As a kid, I remember being packed onto the schoolbus at the end of a bright-blue autumn afternoon, with my little arms buckling under a box stuffed with cooking apples and tins of Heinz ‘cream of tomato’ soup. I was tasked with giving these ‘harvest festival’ goods to an unspecified ‘elderly neighbour’. It was all so bewildering. Not only were all of my elderly neighbours terrifying voiceless spinsters who lurked behind net curtains, I couldn’t stop wondering how you cook an apple, nor how on earth Heinz were managing to cream tomatoes.

I’m just as stupid now. Before writing this piece, I had to Google ‘when is actual harvest festival?‘. It joined the long list of embarrassing questions I’ve asked of Google down the years (generally regarding a new and unexpected medical concern, and often pertaining to precisely how long I have left to live as a result of it).

Apparently, says Google, the true harvest festival should be celebrated on the Sunday nearest to the full moon that’s closest to the September equinox. The exact date of the equinox, warns Google, can vary year to year.

I’ll level with you: I’m still not completely sure when harvest festival is…

All I know is that the very word ‘harvest’ manages to conjure a spirit of goodwill inside me. It feels inherently godly, in the best sense of that word.

Basically, you can forget about full moons and equinoxes. To me, harvest is a drawn out affair, loosely marking the end of summer and the start of autumn. A time of smokestacks and purpling sunsets, for the poets among us.

Whilst researching for my biography of Nelson, one of the things I often ask myself is, if I could go back to his era, what would immediately stand out about his world? Aside from the gag-inducing smells and the fact that nearly everyone was very short and very thin, there is another aspect of it that I often reflect upon, particularly during harvest season.

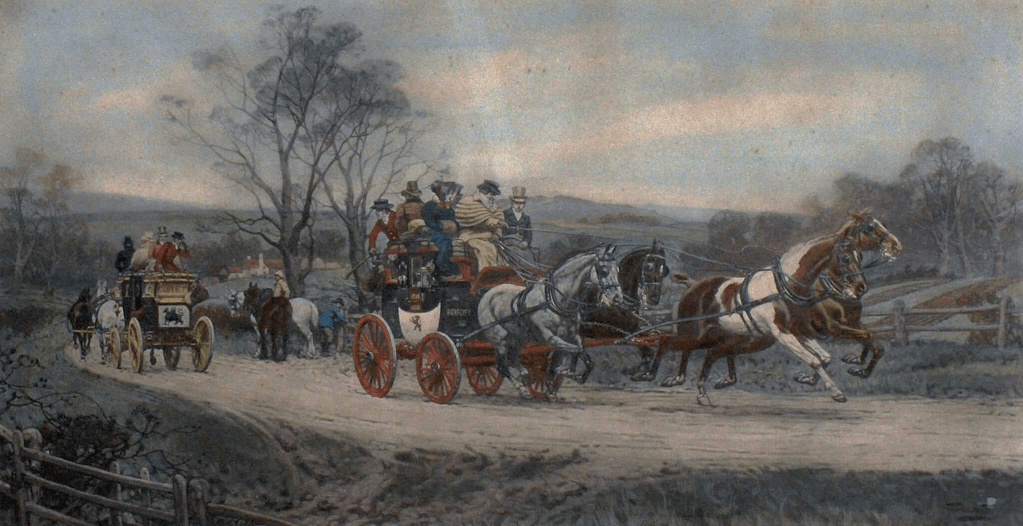

Today, the rural lanes of Nelson’s north Norfolk are coated in bobbly grey tarmac and seemingly trail off to nowhere in particular. But in the 1700s, they were busy thoroughfares of dirt, laced with hoof prints and the slice of wheel tracks. The likes of Nelson’s middle-class family would have often traversed them by carriage, plodding their way to markets and social engagements.

As well as horses and coaches, these roads would have been occupied with scores of roaming nobodies – all now long under the soil in overgrown churchyards – hiking from village to village: young girls heading to the manor house for work; pedlars knocking for custom at cottage doors; vagrants on the slip from their misdemeanours two towns along; friends visiting friends; fishermen trudging home from the sea; and labourers on their way to the fields.

The verges were similarly busy. The roadsides of 2024 are grassy wildernesses littered with Evian bottles tossed from car windows. But they were once populated with farm labourers stopping to recuperate in the shade of the hedgerows, or eating their lunch of bread and cucumber.

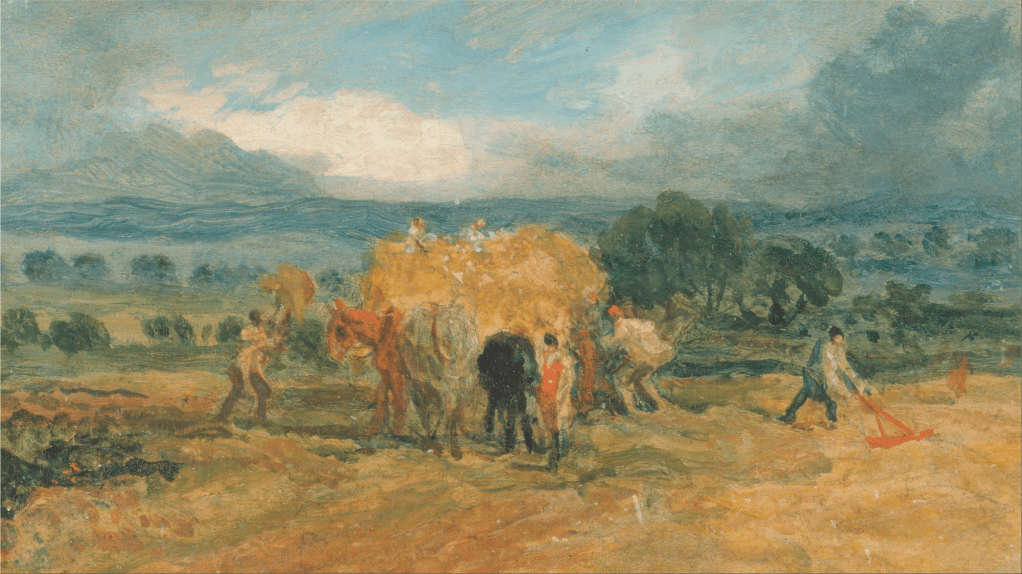

The fields were more alive, too. And not just in harvest time. At various peaks in the agricultural calendar, you could see rows of men, women and children raked across the farmland, bent-double, working the soil.

A commonly romanticised view of farming’s past is that not only was it peaceful, but it was also a joyous operation for all concerned. The vision of a couple of old duffers in flat caps, ambling beside a plough-dragging shire horse, belongs more on a 1000-piece jigsaw than it does in reality. A great many people worked the land, and it was an unforgiving profession. It was also a noisy one. It’s only in the last century that farms have truly quietened down, their barked cries of human endeavour lost to the buzz of a lone, distant machine.

Many things about the past would shock us, but I’d suggest the numbers required to till and toil on farms would come as a particular surprise, were we to see it in action.

In fact, next time you’re zipping through the countryside in your car, listening to Radio 2, I recommend taking a moment to mentally populate not only the road, but the surrounding fields and verges with its ghosts. See if you can imagine the wagons and stagecoaches, the horses tied to posts, the pedlars with their sacks, the labourers laid chatting on the verges, the young children getting their education in bending over to pick things up.

I’d suggest that there’s no better time to do this than harvest time.

So long as you can work out when it is.