The first in a two-part series looking at Horatio Nelson’s school days. Please share and subscribe!

There were two non-negotiable requirements for entry into a Georgian school: money and a male reproductive organ.

The organ had to belong to the individual, but the money could come from anywhere, so long as it materialised. It is likely that Horatio’s school fees were covered by his famous seafaring uncles, Maurice and William Suckling. In future years, Nelson himself would pay for his own nephews’ school fees (an expense he could secretly ill afford).

For most normal Georgians, however, any hope of learning to read relied largely on being taught by one’s parents. The snag was that lots of parents couldn’t read, either. And even if they could, there was little to be read. Books were not only rare, they were expensive. Literature was a rich man’s game.

It was a recurring theme of the 18th century that wealthy people actively feared the idea of an educated underclass. Ignorance was, wrote a contemporary, the ‘opiate of the poor’, a tonic from God to keep paupers content with their station. In his 1785 Principles of Sound Policy, Reverend J. Fawel wrote that, ‘to instruct [the poor] in Reading and Writing generally puffs them with Arrogance, Vanity, Self Conceit and unfits them for the menial stations which Providence has allotted for them’.

Charming.

Over the course of Nelson’s lifetime, things would change. Quicker, cheaper methods of printing made books and pamphlets more readily available. As well as novels and newspapers, numerous guidebooks and how-tos were published. Without anyone having planned it as such, the inns and coffee houses of Georgian Britain effectively became makeshift classrooms in which the poor gradually taught one another not just how to read, but how to benefit from it. Having conquered the basics of reading, many then used guidebooks to teach themselves rafts of new skills, from navigation and philosophy to finance and household management.

Education was no longer limited to schoolboys with wealthy uncles and silly haircuts.

Some Georgian locales were even fortunate enough to have ‘Common Schools’ for the poor. These were built and paid for by philanthropists, rather than the state. More common still, towards the 18th century’s end, were charity or faith schools, often teaching boys and girls basic functional skills – sewing, weaving, ironing, cooking – always with a firm basis on morals.

Learning was direct and simple, often hinging on a rhyme:

It is a sin

To steal a pin

Or:

Swear not at all

Nor make no brawl

Not that going to a private school guaranteed a more rigorous education. Many elite schools were, noted Lord Kenyon in 1795, in a ‘lamentable condition’. Henry Fielding described them as all ‘vice and immorality’, offering, to quote historian, Roy Porter, a ‘diet of birch, boorishness, buggery and the bottle’.

Private school timetables consisted of Latin and Greek language only, with a touch of Latin and Greek history/mythology interspersed. Some establishments might provide a more rounded experience, with additional subjects such as Maths, Science and French, but these were less common.

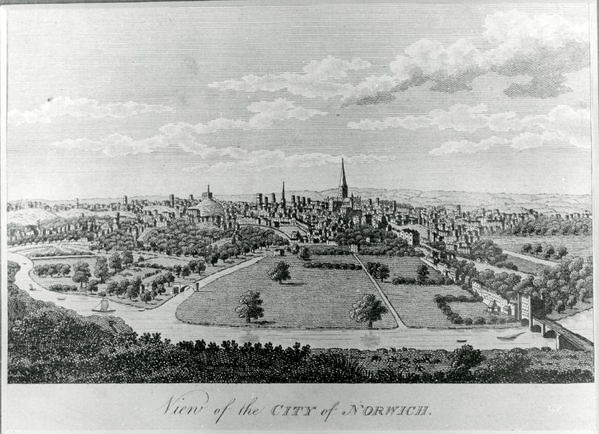

Horatio Nelson’s childhood is foggy, but we do know that his first school was the King Edward VI Grammar in Norwich. In England at that time, Norwich was second in size to London only. By horse, the city was a day from Horatio’s home village of Burnham Thorpe. In many ways, though, it was a distant world.

© Norfolk Museums Service

Norwich’s mighty cathedral still towers above the skyline to this day, but it would have appeared all the more spectacular to a young Nelson in the 1760s. Although familiar with the knockabout ports of Wells and Blakeney, he would never have heard such an endless clattering of merriment, crime and industry. He would likely have never seen such rows of stately town-houses, either, nor walked so many paved roads, nor seen them clogged with so many working horses.

Echoes of medieval money still rang through the Norwich of Nelson’s boyhood. The Industrial Revolution was yet to crack its whip and drive English fortunes north. Horatio would have seen gentlemen hurrying about the city in their multicoloured finery: the bankers, traders, moneylenders, men of letters, weavers, printers, tailors. He would have seen urchins zipping around on errands, prostitutes, drunkards, thieves, vicars, boatmen, and soldiers all populating the city’s wandering crowds of nobodies.

Textiles, shoe-making and general craftsmanship were the big Norwich industries, and many of the men and women employed in them worked from home, sitting in their open doorways. Throughout the city, wooden-framed old Tudor buildings, warping with the weight of extended families, lurched overhead. On the streets, pigeons flapped about in black puddles. Rats darted across shadowed alleyways in gangs. The crumbled walls of forgotten Norman fortifications still lined the routes across town. On seemingly every street corner loomed a mighty stone church.

The King Edward VI Grammar School was nestled in the cathedral grounds, closed off to the throng behind its high walls and opulent medieval gates. Instead of boarding, it’s thought Nelson stayed with an aunt at Suckling House, a stone’s throw from the school. (Today, Suckling House is home to the art-house Cinema City. And the school is still a school, going by the more matter-of-fact name, Norwich School.)

© Norfolk Museums Service

Nelson acquired a decent enough grasp of Latin whilst studying in Norwich, and displayed a quality in his later letter writing that suggested he was educated in a literary style. His High Master was a Mr Symonds and lessons began daily at 7.30am, with canings for latecomers. The rest of his experience can only be guessed at. Certainly, no records exist that suggest this seemingly unremarkable boy would one day warrant his own statue on the school grounds.

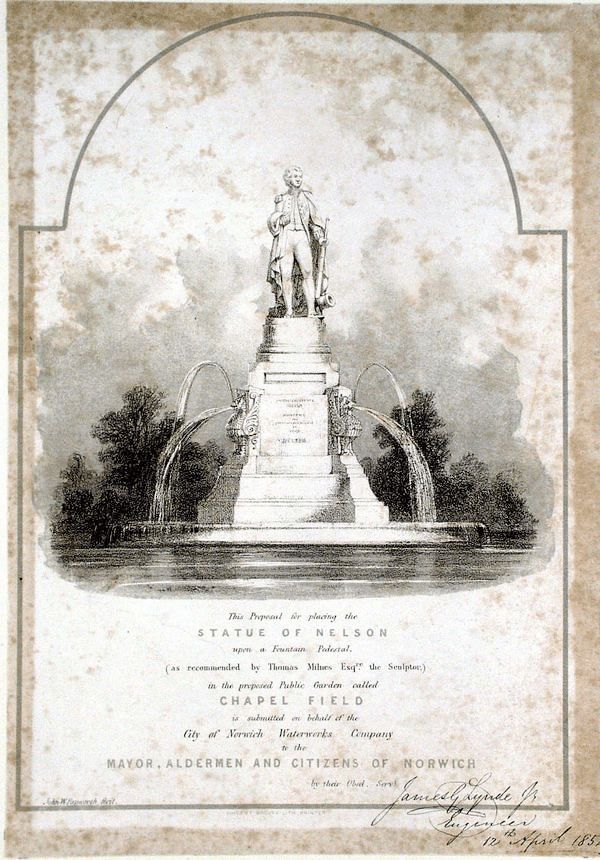

The statue in question (see below) was designed by esteemed Victorian sculptor, Thomas Milnes. It was purchased by the city in 1847 – a good three decades after Nelson’s death at Trafalgar – and was initially plonked between the marketplace and guildhall (ish), bang in the middle of town.

The thing was then lifted from the marketplace in 1856, carried across the city – maintaining its pompous expression throughout – and repositioned in front of the cathedral, facing the entrance to its subject’s former school.

Here it is:

The statue is the kind of depiction of Nelson that I find hard to warm to. It strips him of humanity. It is a cold and grey figure, an admiral with an empty sleeve, looking piously into the distance. His face betrays no evidence of having ever been a schoolboy, or, indeed, fully human. One look at him and you might think he never cracked a playground joke or bit his nails or wobbled a milk tooth or cried to himself under his blanket at night.

Who wants a hero like that?

There had been plans to stick the statue in Chapelfield Gardens and turn Nelson into a water feature. Instead, he was stood outside his former school, where he remains to this day: a former schoolboy worked into a demigod of portland stone.

It’s always the ones you least suspect.

Nelson studied in Norwich for roughly a year (1768-69). His next school was Paston Grammar (now Paston Sixth Form) in North Walsham. I shall post about his time there in the coming days.

Please do share and subscribe!

Plans for the Chapelfield fountain feature.

© Norfolk Museums Service