‘I never expected to return,’ Nelson confided to a friend, regarding his reckless attempt to capture Tenerife on this date in 1797.

A part of him never would. Namely, his right arm.

After a series of failed efforts to capture the island and bloody the nose of the Spanish, the new plan was to attack in small wooden row boats by night, sneaking ashore in great numbers. The attack began badly, with difficulties mooring against the rocks. With the element of surprise forfeited by the almighty racket the British boats were creating, church bells rang out across the island in alarm.

The locals were ready. Snipers slipped into position. Cannon fire coloured the night sky red, whilst musket shots picked British sailors off as they tried to exit their boats. Nearly every house on the island had a marksman firing from an upper window. The soldiers of Tenerife were tough. As were the locals. They intended to hold their keep.

Aboard British ships stationed further back, the wives and young midshipmen – among them Nelson’s young protégé, William Hoste, of Burnham Market (near Nelson’s home village of Burnham Thorpe) – heard the firing in the distance and assumed things were going well.

Many of the wooden boats that had evaded cannon fire subsequently smashed into rocks or filled with the slosh of seawater. Nelson’s own small vessel at least got near the Tenerife sand. He lifted one leg out, into the sea. Before he could even bring his second leg into the equation, something shot at him.

It tore at his right arm, above the elbow. Blood quickly drenched his sleeve. A man beside him caught the same bullet and died instantly, collapsing into the waves and turning the night water purple. Nelson’s young step-son, Josiah, saw his step-father’s distress and tied the wound with a silk hankie (or possibly a sock, or even a neck-tie). He then covered Nelson’s arm with his hat to stop the famous sailor passing out at the sight of his own blood.

‘I am a dead man,’ Nelson cried.

Nelson was rowed back out to sea to board the nearest ship: the Seahorse. He didn’t want to get on it, he said, because there was a pregnant lady on board – Mrs Fremantle – and he could not bear the thought of subjecting her to the sight of his wound; that she should see the famous Nelson in such a state would, he suspected, cause her to worry for her own husband’s fate out on the Tenerife beach. He was told that waiting for another ship could prove fatal:

‘Then I will die,’ he replied. ‘For I would rather suffer death than alarm Mrs Fremantle.’

Legend adds that Nelson refused to board any ship until as many men as possible had been saved from the shore. Eventually, he was rowed to the Theseus. The young William Hoste heard the splashes of their small boat approaching. Leaning over the edge of the ship, he saw a sight that would live with him forever:

‘Him, whom I may say has been a second father to me, his right arm dangling by his side, while with the other he helped himself to jump up the ship’s side.’

Refusing help, Nelson cried ‘Let me alone!’ and pulled himself up the warship’s not inconsiderable side, using his one good arm, while the other hung by its torn sinews. As he boarded the Theseus, the crew took off their hats in salute. This compliment, his step-son Josiah recalled, ‘Nelson returned with his left hand as if nothing had happened’.

‘Tell the surgeon to make haste and get his implements,’ Nelson ordered, conscious of the threat of gangrene. ‘The sooner it is off, the better.’

Everybody knew the ‘it’ to which he was referring. Guns rumbled in the distance.

The surgeons hastily hired for the job were a young Yorkshireman and a French royalist who had joined the British cause against the republicans. There was no time for nerves or second thoughts. Rather than the thin, sterile silver instruments of a modern hospital, their amputation tools looked like something a carpenter might use to turn an oak tree into a staircase. The items would have made a thump as the surgeons spread them out on the table. A select audience loitered in the darkened corners of the operating theatre below deck, hats in hand. Among them stood the ship’s chaplain, ready to pray for the newly deceased.

The sum of Nelson’s anaesthetics was probably a swig of rum beforehand and an opiate pill (laudanum) after. The cleanliness of a doctor’s toolkit varied from man to man. The best way to sum up how primitive an operation this was is to imagine going into your kitchen right now, having a swig of Captain Morgan’s, then attempting an amputation with your best bread knife. It really was as brutal as that.

Nelson was laid down on a bed of sea-chests as the ship rocked and creaked. Lit only by swinging lamps, a new tourniquet was carefully tightened just above the wound. Then, in the heavy silence, the surgeon’s cold blade met the whites and reds of Nelson’s torn flesh. Then, down the implement went, slowly, sinew by sinew. An onlooker fainted.

One Georgian coping mechanism for pain was to bite on a piece of rope or leather. It’s possible Nelson did this, too, screaming to nobody, gagging on his saliva, as the surgeon switched implements to hack at the bone.

The operation was quick. Over in about fifteen minutes. The Yorkshire surgeon noted the details in his logbook:

‘Compound fracture of the right arm by a musket ball passing thro a little above the elbow; an artery divided; the arm was immediately amputated.’

For all its horrors, Nelson’s abiding memory of the operation was of the ice-cold knife first touching his flesh. From that day on, he made a point of telling ship surgeons to warm their amputation blades, lest his men suffer the same ‘coldness of the knife’.

Intoxicated on adrenaline, within half an hour of the amputation, the one-armed Nelson was heard firing fresh battle instructions.

Meanwhile, about three hundred British servicemen had landed on the beach and made it as far as a market square. Armed with sea-sodden weapons and fewer comrades than they might have hoped, they were informed that the Spanish had eight thousand troops in reserve on the island. Even if they had known what was happening to Nelson out on that makeshift operating slab, they might still have wished to swap places with him.

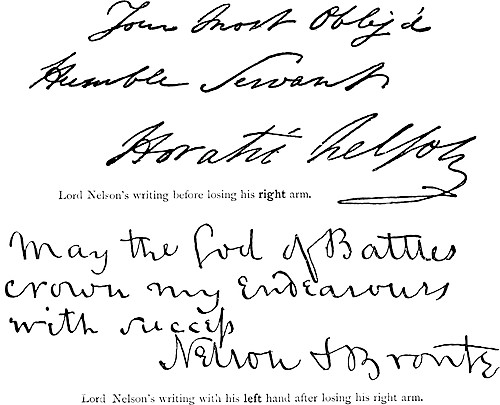

Remarkably, the local governor took pity on the British and not only fed them, but allowed them to leave Tenerife, cap in hand. Small boats were even provided for the surviving sailors to return to their vessels. Additional food was then sent out to the ships. It was not the first time the Spanish had behaved with remarkable compassion. In shaky, almost illegible left-handed writing, Horatio wrote to the governor ‘with most sincere thanks for humanity in favour of our wounded men in your power’.

One of the Theseus surgeons suggested sending Nelson’s right arm to Britain to be buried with ceremony. Nelson allegedly requested it be put to sea with the ‘brave fellow’ who had died beside him from that same crack of gunfire.

‘My pride suffered,’ Nelson later wrote, realising not just the failure of the Tenerife operation but the asinine nature of it. He eventually sailed home on HMS Seahorse, thinking over his next steps. With his one remaining hand, he wrote how he could now only be a burden to his friends and ‘useless to my country’.

About two hundred and fifty men had died in the doomed operation. A hundred had drowned as a result of one ship, the Fox, being struck by a Spanish projectile. Nothing had been gained by their sacrifice.

Few military leaders have careers free from error. But errors were especially costly in the Georgian forces and often resulted in dismissal. In terms of numbers, Tenerife was no Battle of the Somme, but it kept Nelson’s swelling confidence in check.

His letters home reflected a burgeoning depression. In his scrawled handwriting, he wrote that, ‘A left-handed admiral will never again be considered as useful, therefore the sooner I get to a very humble cottage the better and make room for a better man to serve the state.’

Nelson never responded well to failure, especially if he felt he had cost his beloved sailors their lives. It would have felt improbable, maybe even impossible, to him in that summer of 1797 that his two greatest victories – the Nile and Trafalgar – lay ahead.

Historian and Nelson biographer, Andrew Lambert, noted that, ‘the spirit of the age required him to be personally brave’ (2004). Derring-do was indeed the done thing in the Georgian navy. As noted at the top of the piece, he himself had expected to be killed during the mission.

Maybe Nelson’s real bravery came in taking full responsibility for Tenerife in his official dispatches, avoiding mentioning other highly culpable parties in his letters to the Admiralty. This willingness to bear the brunt would stand him in good stead; in later battles, when he encouraged his captains to use initiative, they did so knowing that Nelson would take the flak for their failings.

George III wrote furiously to the Admiralty, demanding clarity regarding the levels of intelligence obtained before letting Nelson loose on Tenerife. The king said he did not enjoy ‘empty displays of valour when attended with the loss of many brave men and no solid advantage gained by their exploits’.

It was hard to argue with him. Criticism from the king would have hurt Nelson deeply.

Horatio Nelson had now lost an arm and damaged an eye. Neither injury had occurred in a traditional sea battle, but in largely pointless land manoeuvres. Biographer, Terry Coleman, wrote in 2005 of Nelson’s ‘perfect fearlessness’.

There was an imperfect recklessness, too.

The British public never forgave Nelson for Tenerife. But that’s because they never blamed him for it. To his surprise, he returned a hero, a man of action who led from the front.

When given the Freedom of the Borough of Great Yarmouth years later, the town clerk asked Nelson to put his right hand on the Bible.

‘Ah,’ Nelson is said to have quipped. ‘That is in Tenerife.’

He had learnt the value of a visible war wound.

Share this post and subscribe for regular Nelson updates. Let’s keep Nelson’s story alive.