It was on this day – July 12th – in 1794 that Horatio Nelson suffered lasting damage to his right eye.

That summer, Nelson had been tasked with blockading and harrying an island in the Mediterranean. It was a small island, roughly equidistant between Italy and southern France. Nelson knew its name well.

Corsica.

The previous year had seen a twenty-four-year-old Corsican general make a name for himself in mainland France by inspiring the bloody Siege of Toulon, in which French Republicans recaptured Toulon’s port from the Spanish and British.

‘Each teller makes the scene more terrible,’ Nelson wrote home to his wife, upon meeting with haggard Toulon evacuees. ‘Fathers are here without families, families without fathers.’

Nelson’s mouth watered, he added, at the prospect of leading a counter-attack against the French Republican army and their cocksure young leader, referred to as ‘Buona Parti’.

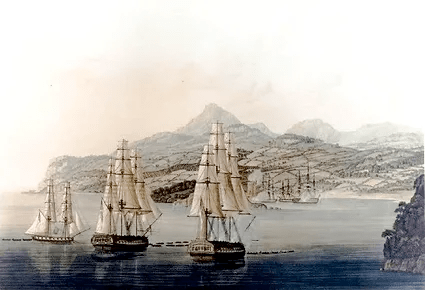

With his latest directive from the Admiralty, the chance for Nelson to lay a glove on the Corsican now presented itself. The plan was to blockade Napoleon’s home island, pepper any resistance with cannon-fire, and starve it into submission. At which point, the Royal Navy could set up its own port.

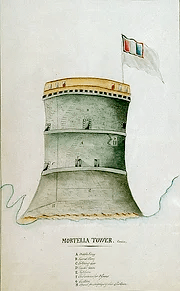

After months of slow progress on the blockade, rumour swelled of a physical siege on Fort Bastia, one of the island’s strongholds. The fort had recently been captured by French Republicans, whose new tricolore flags lolled in the humid air. The English Army were against the idea of a siege. The Navy, under the command of Lord Hood, felt otherwise. Lord Hood had overseen – and been largely blamed for – the disastrous retreat at Toulon and was eager for a victory. Nelson, too, thought that not attempting to capture the fort would be a ‘national disgrace’ and said he would sooner die than sit back.

‘Cowards die many times before their deaths,’ so went Nelson’s favourite line from Julius Caesar. ‘The valiant never taste of death but once.’

Dying was not to be feared. Especially in battle. Men, Nelson wrote, should ‘recollect that it is the will of Him in whose hands are the issues of life and death’.

Always believing his ships’ crews to be better fighters than land soldiers, Nelson claimed that with just ‘500 sailors’ and his ship, Agamemnon, he could complete the capture of Fort Bastia. Lord Hood shared Nelson’s confidence. And, as this was a naval operation, Hood could call the shots. A plan was devised to bombard Fort Bastia with cannon fire, then attack on foot with over a thousand men.

‘They hate us sailors,’ Nelson once said of the English army generals. ‘We are too active for them. We accomplish our business sooner than they would like.’

In fact, if it were up to him, Nelson would have had the Army remove all of its troops from the European mainland, allowing the Navy to conduct – and win – the war by itself. Fighting on the waves was, he said, ‘The only war where England can cut a figure’.

Wars have a proud tradition of choosing scenic backdrops, and Corsica was no exception. Olive trees and lemon groves. Rolling hills of vineyards and roaming wild goats. Blue skies and seabirds. Little villages of white, sun-kissed villas dotted about in the distance. An oil painting of a warzone.

‘The most romantic view I ever beheld,’ Nelson said of it, unaware that his ability to appreciate romantic views was about to become 50% less effective.

Before they could take the fight to the French, the English had to set up battalions and build makeshift pathways to navigate their heavy guns into positions up the picturesque hillsides. The endeavour of Nelson’s mostly Norfolk-born crew of sailors raised the eyebrows of onlooking locals (as, most likely, did their accents). Horatio himself seemed indefatigable. The work had the desired effect: upon seeing the Navy’s ships in the surrounding waters, and the cannons on the hillside, the French surrendered Fort Bastia before the fighting truly got going.

The four thousand French surrendering to the English thousand was, Nelson said (once again tempting fate regarding his eyes), ‘the most glorious sight that an Englishman could bring about’.

With Fort Bastia secured, attention was turned to Fort Calvi, further along the coast. A similar plan was adopted: encircle, threaten, then bombard the stronghold and attack on foot, if required.

The hills and valleys en route to Calvi were more troublesome, though. The mission was beset by torrential storms that lasted days and promised to make a wreck of the supporting ships in the bays. So difficult was it to drag the cannons through the foliage that one sailor cheered upon completing the task. As he shouted, a sniper’s bullet tore through his skull. The mission now felt decidedly more dangerous.

Whilst out walking amongst the hillside battalions, Horatio caught what felt like a hard slap to the face from nowhere. What was it? A stone? A bullet? It slashed his skin, near the right eye. Blood ran down his cheek.

It transpired that a stray French shot had hit either a cliff face or a sand bag and sent debris flying. ‘Within a hair’s breadth of taking my head off,’ Nelson said of it.

He initially described the impact as leaving only ‘a very slight scratch’, but the wound had compromised his vision. From his right eye, he would evermore see only extreme light and dark.

It’s likely that the long-term effects on his eyesight were psychological. It may have been the fear of blindness – possibly stemming from having to watch his short-sighted father stumble into the door-frame twelve times a day – that made Nelson think his own vision was damaged. He joked about the injury, declaring ‘So my beauty is saved!’ when he saw that he had not been damaged aesthetically.

At the age of thirty-five, Horatio Nelson had acquired his first noteworthy war wound, albeit one suffered in vaguely slapstick circumstances. Regardless, the first truly iconic Nelson feature was in place.

Although he seldom wore one, Nelson would forever be associated with eyepatches. To say he never wore one, though, would be untrue. He occasionally sported a green protective shield, and had a patch attached to one of his hats (albeit to keep the sun out of his good left eye). The National Maritime Museum has what is thought to be one of his patches in their collection (see below).

Long after Horatio Nelson died, Victorian artists found it difficult to resist painting him with a patch. It helped portray him as the wounded hero, the gritty Englishman fighting the odds. The legend was hammered home when Sir Laurence Olivier played him, fully eye-patched, in the 1941 propaganda movie, That Hamilton Woman.

‘We are few, but of the right sort,’ Nelson had said of his men at his fateful visit to Corsica.

The attacks at Bastia and Calvi were ultimately fruitless, however. The forts were recaptured soon enough and despite the cheers from the newspapers and the man on the street back home, those in the know thought the mission reckless. It could be seen, like many of Nelson’s escapades, as either a bright burst of glorious English sunshine in a period of defeats or a dark, disastrous foray into reckless, egotistic heroism.

It all depends on which eye one views things from, of course.