Nelson’s mother, Catherine, died suddenly at home on Boxing Day, 1767, aged just forty-two. It is thought she died of pneumonia or an ague – arrested by the bailiff of the marshland, as the local saying went – but her eldest daughter, Susannah, later wrote how her mother had bred herself to death. Eight of Catherine’s eleven children survived her. Horatio was nine years old. The youngest, Kitty, was nine months.

Five days later, Catherine’s mother, Ann Suckling, also succumbed to the bailiff’s clutch, aged seventy-seven. She had been an ever-present in the Burnham family home. As Rector, Edmund Nelson had to conduct both funeral services alone on stone-cold winter’s afternoons in Burnham Thorpe church, then walk through the village to his eight children in a darkness brightened only by a fierce frost.

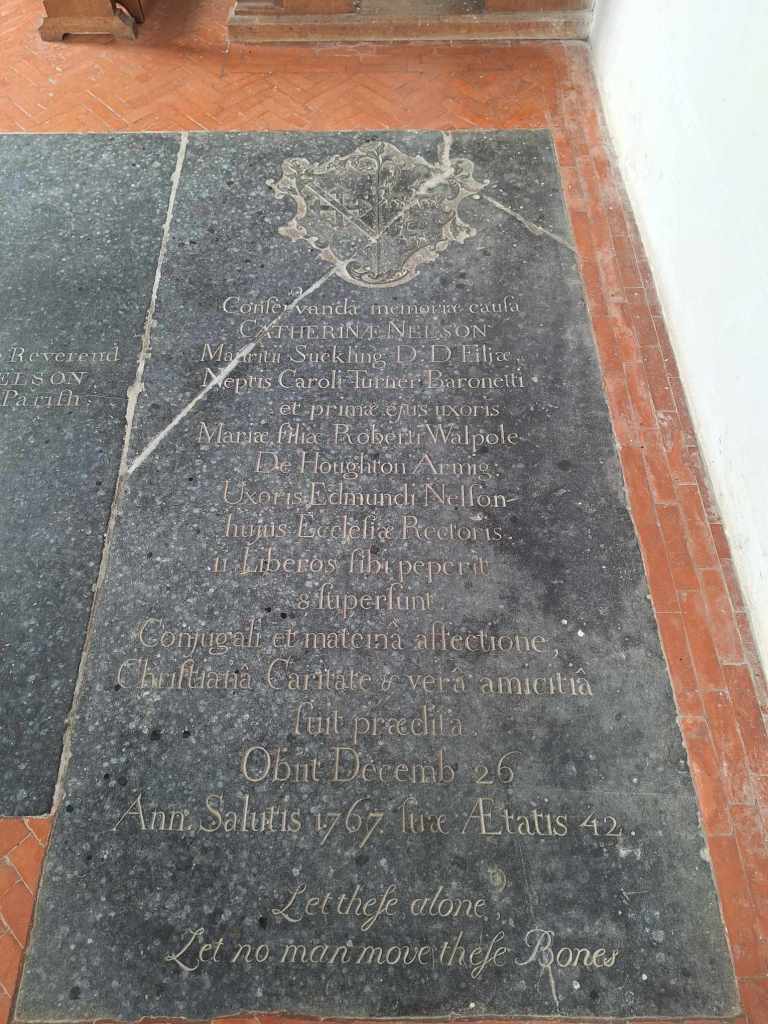

Catherine Nelson was laid to rest under a black slab in the All Saints’ chancel. Its Latin inscription reflected a deliberate attempt by Edmund to honour her noteworthy family connections. At the foot of the stone, read a more sombre message in plain English:

Let these alone

Let no man move these Bones

You can just about make the words out here (look towards the bottom):

Catherine’s brother, the famed sailor, Maurice Suckling, vowed to assist in providing opportunity for Edmund’s boys. The eldest was to go straight into work at the London Excise Office, aged fifteen. Similar vacancies could doubtless be filled by the other Nelson sons, including Horatio, once they’d been schooled. Something clerical. Quill and ink. Something safe.

The death of Horatio’s mother is a tragedy cloaked in secrecy. He maintained a lifelong tight-lip on the matter. One of his two known recollections of her was that she ‘hated the French’. Starved of much else – and ignoring that hating the French was nigh on a national pastime for Georgians – it is tempting to project meaning onto this revelation and see his mother’s hatred as a guiding force for Nelson’s chosen career of aiming cannons at their ships. There is precious little else for biographers to work with.

It’s a reasonable assumption that Catherine encouraged careers at sea for her sons, seeing the success it had brought for her own brothers. Indeed, her first daughter, Susannah, recalled having sucked a love of the Royal Navy ‘with my mother’s milk’.

‘The thought of former days,’ Horatio wrote to a Burnham friend from aboard the HMS Victory in 1804, ‘brings all my mother into my heart which shows itself in my eyes.’

In all his thousands of letters and dispatches, this burst of emotion – a slight misquote from Shakespeare’s Henry V – is the second, and final, of Horatio’s recorded references to his mother. The rest, as the Bard might put it, is silence.

For the five siblings he would ultimately outlive, Horatio Nelson mourned little more. His strongest sibling bond in childhood was with William, who was just one year older. But his closest lasting bond was with Kitty, his youngest sister. Of the family, the pair shared the best physical resemblance to their mother.

‘My small income shall always be at her service,’ Horatio would one day write of Kitty, ‘and she shall never want a protector and a sincere friend while I exist.’

Although known as Kitty – or ‘Katty’, by Horatio – his favourite sister had, of course, not been christened as such.

Her name was Catherine Nelson.